Learning Theories

Module 1

Behaviorism

Behavioral theory focuses on the way humans learn through interaction with their environment. Behaviorism solidifies the fact that behaviors are learned through conditioning. Skinner mentioned that conditioning is a procedure that utilizes punishment and reinforcement. The behavioral model provides an organized approach to teaching, allowing educators to set clear expectations and provide consistent routines. Behavioral theorists believe there is a certain way to do tasks to cultivate a desired outcome, and the teacher determines what that looks like (Samoila et al., 2023).

Example

This theory can be applied to student behavior plans. Many students thrive with positive

They can better interact in school when their positive behaviors are rewarded (Bright, 2023). For example, if a young student struggles with speaking out inappropriately in class, they may have a positive behavior plan to encourage them when they appropriately follow classroom expectations. The plan could state that when the student does the desired task of raising their hand before asking questions, the teacher will thank them for raising their hand and waiting to be called on before speaking.

Reference(s)

Bright, K. (2023, September 21). Behaviorism in education: How to foster learning environments. LearnLever. https://learnlever.com/behaviorism-in-education/

Samoila, C., Ursutiu, D., & Munteanu, F. (2023). The remote experiment in the light of the learning theories. International Journal of Online & Biomedical Engineering, 19(14), 26–44. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijoe.v19i14.43163

Cognitivism

Cognitivism theory focuses on the internal process of learning. These processes are “memory, attention, perception, and reasoning” (Khalil, 2025). Learners can make meaning of what they are learning, process it internally, and then create a response; it is not as simple as input = outcome. Major theorists associated with cognitivism are Wertheimer, Kohler, and Koffka, who led the Gestalt movement. They solidify the idea that learning isn’t just a mechanism, but a combination of “forming associations between small pieces of knowledge that facilitate the acquisition, storage, and recall of information in memory” (Khalil, 2025). This model promotes the cognitive aspect of learning and reinforces the idea that learners exist independently in their learning processes.

Example

A great way to focus on the importance of the cognitive process is through chunking. In the presentation, McKay explains that “chunking the material into smaller pieces is a good way to design [in relation to the constructivism theory]” (American College of Education, 2025). Through “chunking”, teachers can break down complex and large skills into individual tasks for learners. Since cognitivism is based largely on internal processes such as memory, taking a small part of a whole can help learners memorize things better through connection. For example, I am teaching Tommy Orange’s text There, There in one of my classes. My goal at the end of the unit is for students to discuss how identities in the text relate to their own identities. Before I can get to that end goal, I need them to understand where identity appears in the text. I would take an excerpt from the novel that discusses the topic of identity and give students time to identify where they see identity appear in the excerpt.

Reference(s)

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 1 [Part 2 Presentation]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

Khalili, H. (2025). Learning theories and their applications in interprofessional education (IPE) to foster dual identity development. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 39(3), 338–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2025.2496325

Constructivism

Constructivism theory is defined in many ways, with some researchers claiming that it has become “almost…undefinable” (Null, 2004, p. 180 as cited in Kretchmar, 2021). There are two main “strands” of constructivism, Jean Piaget’s cognitive constructivism and Lev Vygotsky’s social constructivism (Kretchmar, 2021). These theories emphasize that learners construct their knowledge through their cognitive and social experiences. This model can allow educators to model the active-learning process, posing content for students to make their own understandings and goals.

Example

An example of where this theory applies is seen in a lesson from Schifter. A first-grade teacher outlined the size of a boat with masking tape on the floor of a class, and students were asked how they would measure the size of the boat. Students created their own measuring system based on one classmate’s foot size. The teacher then asked the students why they felt it was important to develop a standard unit of measurement. After they reflected, they noted how it would be too inconsistent to use different hands, feet, etc. (Schifter as cited in Kretchmar, 2021). The teacher didn’t give the students a goal, they gave them a problem to solve and construct their own meaning. (Kretchmar, 2021).

Reference(s)

Kretchmar, J. (2021). Constructivism. Salem Press Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://research.ebsco.com/c/36ffkw/viewer/html/qu6ghw4epr

Connectivism

Connectivism theory revolves around the idea that people have so much new information and it fundamentally changes the way people learn. People are directly connected to subject experts and a great deal of information, so the “learning process is faster and more fluid than in the past and lasts throughout life” (Ungvarsky, 2024). Writer George Siemens and philosopher Stephen Downes are credited with the development of the connectivism theory. The core of this theory is to explain how connections made by technology change the way people learn, requiring a sort of pre-learning. Educators focus on students’ learning through connection, not just through personal experience (Ungvarsky, 2024).

Example

An example of this theory in practice is the format of this class. We participate in a class discussion every week in an online format where we learn and share concepts with one another. Optimally, the connections we make in online discussion posts should strengthen or redefine our understanding of the content. Harry Cloke references Siemens’ 8 principles of connectivism, one being that “learning is a process of connecting specialized nodes or information sources” (Cloke 2024). The nodes are the students. That’s why it’s beneficial to have the first post done by Thursday, so students have “nodes” or “posts” to continuously draw meaning from and engage with.

Reference(s)

Cloke, H. (2024, June 27). Connectivism learning theory: Your guide to learning in the digital age. Growth Engineering. Retrieved from https://www.growthengineering.co.uk/connectivism-learning-theory/

Ungvarsky, J. (2024). Connectivism. Salem Press Encyclopedia. https://research.ebsco.com/c/36ffkw/viewer/html/2ukzgvrosz

Pedagogy vs. Andragogy

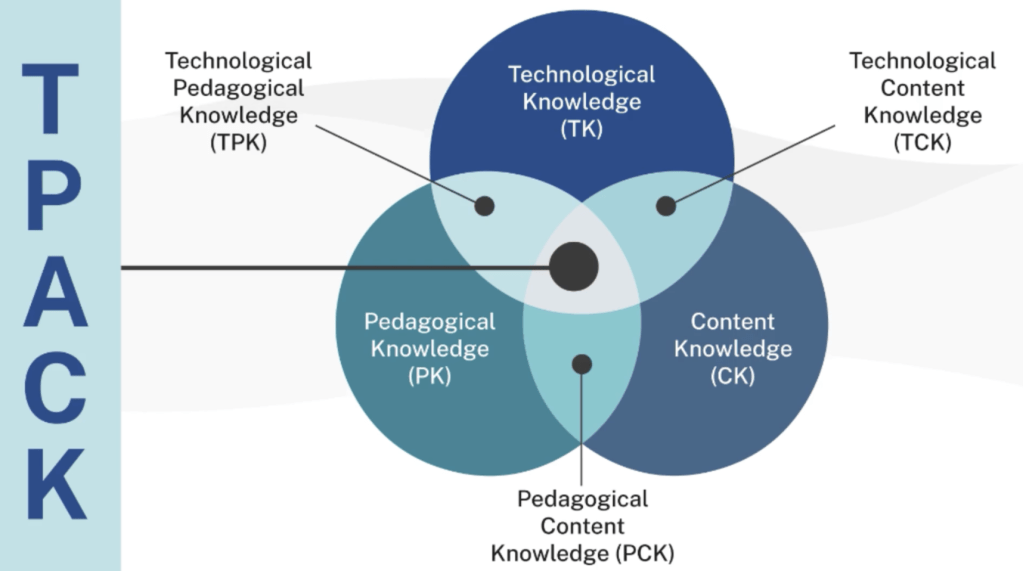

TPACK | Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge

TPACK is a framework that acts as a guide for educators when using technology in learning. Educators use this to effectively join technology with teaching pedagogy and content. TPACK is based on Shulman’s fundamental model of content knowledge, pedagogical knowledge, and pedagogical content knowledge. Technological knowledge was added by Mishra and Koehler to finalize the framework as TPACK (Prasetya & Irwanto, 2025). Prasetya & Irwanto (2025) identified the seven interconnected domains as follows:

- TK (Technological Knowledge): understanding of various technologies, traditional and digital

- CK (Content Knowledge): understanding of the subject matter

- PK (Pedagogical Knowledge): having expertise in designing instructional activities, classroom management, and assessment methods

- PCK (Pedagogical Content Knowledge): using effective strategies to teach specific content

- TCK (Technological Content Knowledge): how digital technology can be used to present subject matter

- TPK (Technological Pedagogical Knowledge): how technology can enhance teaching practices and motivate students

- TPACK (Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge): Putting all the prior domains together. The final step integrates technology, pedagogy, and content into a cohesive approach to create meaningful and effective learning experiences (Mishra & Koehler, 2006 as cited in Prasetya & Irwanto, 2025).

TPACK Venn diagram in Module 1, Presentation 3

[Figure 1] Note. From American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 1 [Part 3 Presentation Infographic].

Example

I’ve unknowingly used TPACK countless times as an educator. An example would be during a characterization unit where students read The Great Gatsby. I had students pick a character from The Great Gatsby and make a social media account for that character. We used the social media platform Instagram, but it could easily be adapted to TikTok or Twitter based on student interest. I have a good understanding of these platforms and how a persona is created by the type of content and language on an account. Students can reflect on their character’s actions, analyze how they would convey them, and then actively create a profile using their understanding of both the character and social media.

Reference(s)

Prasetya, A., & Irwanto, I. (2025). Research trend on Technological Pedagogical and Content Knowledge (TPACK): A bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science, and Technology, 13(3), 638–669. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijemst.4808

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 1 [Part 3 Presentation Infographic]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

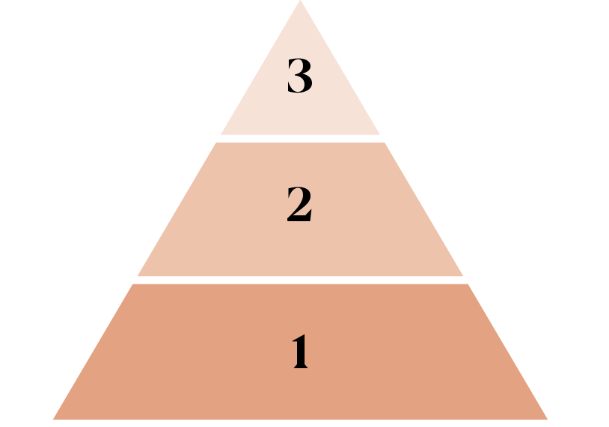

TAWOCK | Technology Andragogy Work Content Knowledge

TAWOCK is the adult version of TPACK. Adult learners are more goal-oriented than children, making the approach a little different. Three levels make up the conceptual framework: Pedagogy, Andragogy, and Heutagogy. At the first level (pedagogical), learners listen and are engaged. At the second level (andragogy), learners are independent and goal-oriented. At the third level (heutagogy), learners apply their learning to their personal lives (American College of Education, 2025).

TAWOCK figure in Module 1, Presentation 3

[Figure 2] Note. From American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 1 [Part 3 Presentation Infographic].

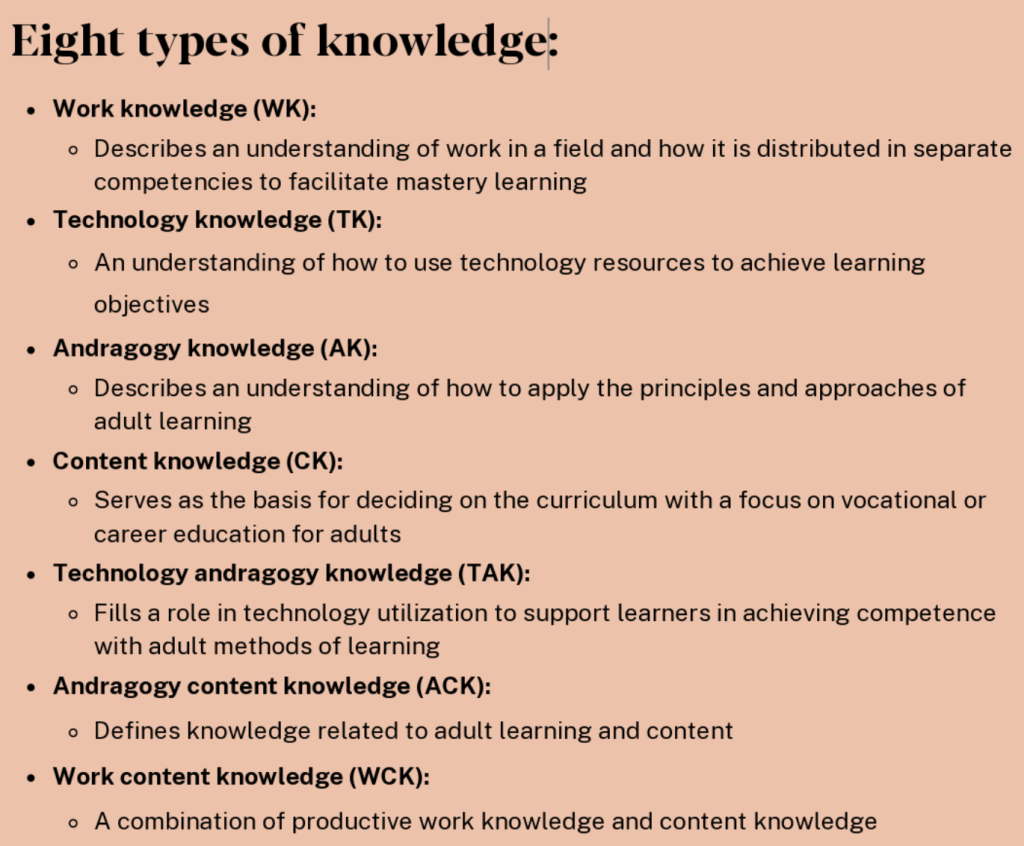

The second part of this framework is how all the types of knowledge fit together. There are 8 kinds of knowledge listed below.

TAWOCK 8 Types of knowledge infographic in Module 1, Presentation 3

[Figure 3] Note. From American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 1 [Part 3 Presentation Infographic].

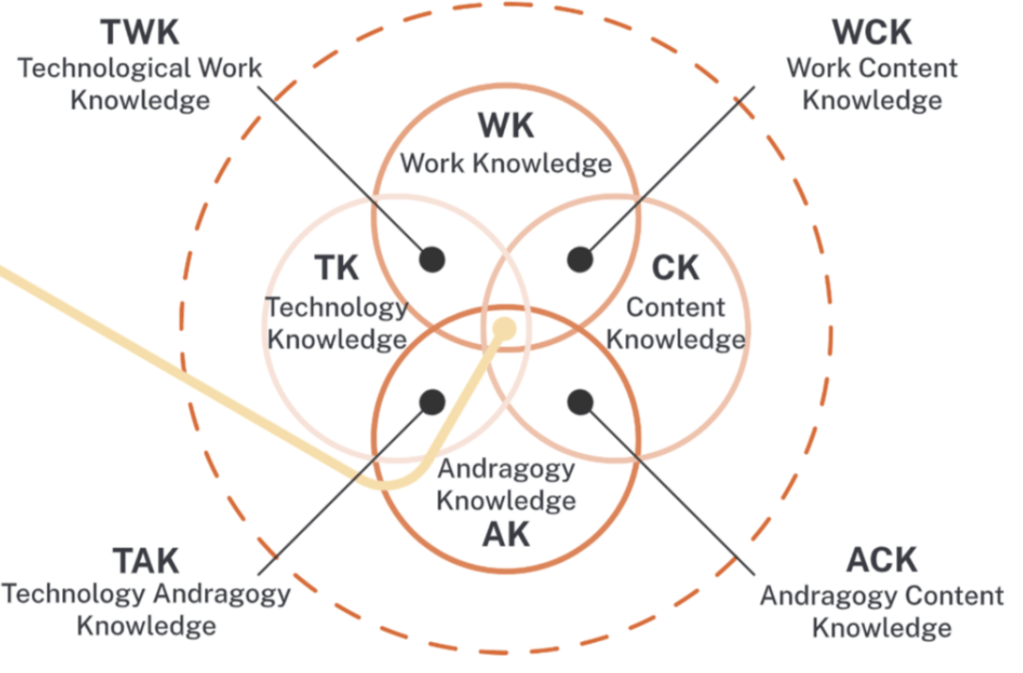

The way this knowledge is connected is in a quadruple Venn diagram. An example of the diagram is pasted below.

TAWOCK 8 Types of Knowledge figure in Module 1, Presentation 3

[Figure 4] Note. From American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 1 [Part 3 Presentation Infographic].

Example

An example of TAWOCK could be an effective, online professional development course. All K-12 teachers take professional development courses throughout the school year. Many educators struggle to find the work beneficial because it lacks acknowledgement of their pre-existing vocational knowledge. That is where creating a course using the framework of TAWOCK serves effectively. Say a school wants teachers to learn about new grading technologies offered by a school district. Instead of holding a meeting where teachers look at slideshows of what the new technology is and how to use it, there could be a technologically driven exploration of the technology on the teachers’ end, with mini units where teachers practice integrating the technologies in their classrooms. This is different than being given new technology and being told to try it. A course like this serves to connect learners to the content, so they can use it in a meaningful way not only for school needs, but for their own personal uses.

Reference(s)

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 1 [Part 3 Presentation]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

Prasetya, A., & Irwanto, I. (2025). Research trend on Technological Pedagogical and Content Knowledge (TPACK): A bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, 13(3), 638–669. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijemst.4808

Learning Process Models

Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory

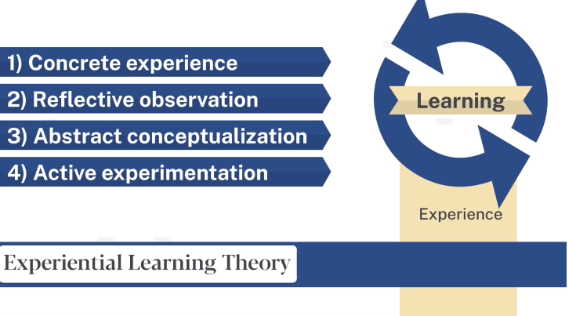

Kolb’s experiential learning theory theorizes that “individuals learn by reflecting on concrete experiences, extracting lessons and applying what they learn to new experiences” (Matsuo, 2025). There are four stages to this process, as stated in the module 1 presentation. The first stage in the learning process is the concrete experience. The second stage is reflective observation about that experience. The third stage is abstract conceptualization. This is the stage where people take what they reflected on from their experience and connect it to something else. The fourth and final stage is active experimentation. This cycle repeats for all learners (American College of Education, 2025).

Kolb’s experiential learning experience cycle in Module 1, Presentation 4

[Figure 5] Note. From American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 1 [Part 4 Presentation Infographic].

Example

This theory can be seen when anyone learns a new task for the first time. An example is seen in part 4 of the ACE TECH 5203 Module 1 presentation. There is a person who learns how to play the piano who has never played piano before. Their first lesson is the concrete experience. The second stage is reflective observation, where the person thinks about what they learned in the lesson. The third stage is where the person begins to recognize patterns in piano playing. Finally, in the last stage, they apply the concepts learned and begin to introduce new techniques. This cycle continues the more the person plays the piano, leading to authentic learning (American College of Education, 2025).

Reference(s)

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 1 [Part 3 Presentation]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

Matsuo, M. (2025). Supporting experiential learning for expanding successes: Extending Kolb’s model. Human Resource Development International, 28(3), 423–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2024.2401301

Gagne’s Nine Events of Instruction

Both Gagne and Kolb’s theories work together to create “engaging and compelling learning experiences” (American College of Education, 2025). Gagne’s nine events of instruction focus on how to instruct based on what happens inside the mind of a learner when faced with an external issue. The nine events are listed in order as…

- Gaining attention

- Stating objectives

- Stimulating recall of prior learning

- Presenting the content

- Providing guided learning

- Eliciting performance

- Providing feedback

- Assessing performance

- Enhancing retention and transfer (McNeill and Fitch, 2023).

Practical ways of applying this research include chunking or micro learning. Breaking down steps for students will aid in providing transparent structure for both the learner and educator. (McNeill and Fitch, 2023).

Example

An example of Gagne’s nine steps can be seen in skill acquisition in a classroom. The following is a table that has each step of this process with an example next to it. The goal is for students to be able to identify arguments in visual texts and understand a call-to-action. This would be done during a rhetoric unit in a 10th grade IB classroom.

| Event | Example |

| Gain Attention | Provide the class with a gallery walk of visual texts like advertisements and ask how the works make them feel |

| Explain Objectives | Explain to students they will be identifying arguments in visual texts to understand the call to action. |

| Stimulate Recall | Ask students if they have ever seen visual texts and “felt” something from them |

| Present Content | Define what a call to action is and give students posters from this website. https://amplifier.org/ |

| Provide Guidance | Pick an example with the class and model how certain colors, words, symbols, etc. help convey meaning and WHY the author wants to convey said meaning. (Model and then gradual release of power) |

| Elicit Performance | Students in small groups pick an example of a poster and analyze what the argument is, what helped them discover that, and why the author created it. |

| Provide Feedback | Check each group to see if they did all three parts. If you see there is something done incorrectly, praise a positive, identify the negative, and then offer advice on how to complete the rest. |

| Assess Performance | Have students individually explain how they determined the link between argument and call to action using visuals. |

| Enhance Retention | Have students individually select a poster they are interested in and have them complete steps 5-8 independently. |

Reference(s)

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 1 [Part 3 Presentation]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

McNeill, L., & Fitch, D. (2023). Microlearning through the lens of Gagne’s nine events of instruction: A qualitative study. TechTrends: Linking Research and Practice to Improve Learning, 67 (3), 521–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-022-00805-x

Continuous Improvement

PDSA Cycle | Plan Do Study Act Cycle

The PDSA Cycle is a “systematic process for gaining valuable learning and knowledge for the continual improvement of a product, process, or service” (Montague, Brewer, Reid, & Kohlmeyer, 2024). This cycle requires instructional designers and educators to plan the content, deliver content, assess how participants understood the content/what was missed, and make changes to the course based on how the participants did. This cycle is a continual process and reaffirms the importance of reflection and action within the design process (American College of Education, 2025).

Example

An example of this cycle can be seen after administering a formative assessment in the middle of a unit in a high school Journalism class. A teacher would begin a unit with students and present the 4 goals that will be met by the end of the unit, which are the basics of reporting, the basics of photography, the basics of the design platform, and the basics of story writing. Students would then partake in classroom activities to build towards their goals. The teacher would then give a formative assessment of the 4 main skills. If the teacher sees that most of their students are struggling with reporting, they will change their future instruction to focus on that skill, so students have a better understanding by the next assessment. They would also go back and change assignments relating to the reporting section so that next year’s class will have a better understanding of the skill by that point than the previous class. This cycle continues on and on for all skills after assessment.

Reference(s)

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 1 [Part 3 Presentation]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

Montague, N. R., Brewer, P. C., Reid, L. C., & Kohlmeyer, J. M., III. (2024). Helping your students overcome cramming using an adapted version of W. Edwards Deming’s Plan- Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle. Issues in Accounting Education, 39(3), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.2308/ISSUES-2021-028

Design Models

Module 2

Instructional Design (ID) vs. Learning Experience Design (LXD)

Instructional Design (ID) and Learning Experience Design (LXD) define an approach to creating a learning experience. Design includes understanding the audience’s needs and goals to create learning activities and effective content delivery. The two methods are complementary and do not have to exist exclusively. ID emphasizes learning and supports a step-by-step process for developing instruction. Typically, instruction is driven by learning objectives, direct instruction, and uses traditional assessments to evaluate learning. LXD has an integrated approach with a heavier emphasis on emotional, social, and cognitive aspects of learning. In LXD, the focus is on integrating hands-on and collaborative instruction that often utilizes technology. According to Floor (2023), “A great way to explain the general difference between LXD and ID is by comparing a scientist to an artist” (para. 2). Like a scientist, the instructional designer follows a methodical process with clear objectives and measurable results. Meanwhile, the learning experience designer, like an artist, creates engaging, emotionally rich experiences that connect with learners on multiple levels beyond just transferring information.

Example

An example demonstrating the difference between ID and LXD can be illustrated in a professional development session with school staff. The staff will receive training on the new Assessment Feature in the school’s LMS.

| Instructional Design (ID) | Learning Experience Design (LXD) |

| The staff is presented with the learning objective to learn the new online feature. Staff are required to use online assessments to collect data. ¯ The instructor demonstrates the skills and steps to complete the goals. ¯ The staff members try the step-by-step implementation as guided by the instructor. ¯ Staff have begun using the new online feature in their classrooms. Instructors and administration evaluate and hold staff accountable for carrying out the directive. | The staff is presented with a problem that needs to be solved. The administration needs a way to collect data as students complete formative work. The staff are given the new online assessment feature on the LMS as a possible option. ¯ The staff begins to explore the LMS and its features to experiment with how it works and what it can do. As they explore, they create lists of pros and cons. The staff notes items for which they need further training or exploration. ¯ Through collaboration, the staff determines that the online LMS is the best way to collect data. The staff begins using the assessment feature to collect data. ¯ As the data are collected, the administration and staff evaluate the effectiveness and adjust accordingly. |

Reference(s)

Floor, N. (2023, November 9). Learning experience design vs instructional design. Learning Experience Design. https://lxd.org/news/learning-

First Principles of Instruction

Merrill’s Principles of Instruction

Merrill’s Principles of Instruction are based on learning through problem solving as opposed to taking in large amounts of information at once. There are 5 main principles for this design: task-centered approach, activation, demonstration, application, and integration. (American College of Education, 2025). The purpose of this model, like many others, is for people to actively engage in their learning and apply it in the long term. This model is great for engaging a wide range of learners because a designer must begin by choosing a real-world problem (the task-centered approach). In the second principle of the design, designers apply learners’ existing knowledge to the new knowledge they’re learning. This helps in meeting learners’ needs because IDs need to directly look at what is needed from their learners’ existing knowledge to get them where they need to be. In principle three, demonstration, educators demonstrate the task in a way that’s clear to them (further illustrating the importance of accounting for learners’ broad identities). The fourth and fifth principles, application and integration, respectively, require learners to complete the task on their own with their previous knowledge, directly relating to the students’ goals and processes of learning. (American College of Education, 2025).

Example

These principles aren’t exactly a model by themselves, but parts of a model that need to be applied in a framework when designing instruction. After reading a journal article on gamification utilizing Merrill’s principles of design, Esterhuizen, Drevin, Snyman, and Drevin (2022) explain “a principle in this context is a relationship that is always true regardless of the environment it is applied within.” Essentially, these principles can be applied independently or in combination with other frameworks. As a softball coach, I could see myself using all 5 principles when explaining new skills to players. While my example isn’t necessarily a technologically based design model, it adheres to Merrill’s key principles. If a coach were to use all the principles in one design (technically, the four-phase cycle), it could look as follows.

| Principle | Example |

| Task | Players are to learn how to throw on the run. |

| Activation | Players already know the mechanics of shorthand throwing and footwork associated with a typical throw. They need to activate this knowledge to connect it to the new footwork they will be shown to complete the task. |

| Demonstration | Coach would demonstrate a throw on the run using the players’ understanding of shorthand throws and the new footwork associated with it. |

| Application | Players would then try to throw themselves. After multiple attempts, the footwork would shift to become the focus. |

| Integration | Next, the appropriate footwork and timing would be integrated with the shorthand throw they’re already familiar with. |

Reference(s)

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 2 [Part 3 Presentation]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

Esterhuizen, J., Drevin, G., Snyman, D., & Drevin, L. (2022). Linking gamification, ludology and pedagogy: Principles to design a serious game. International Association for Development of the Information Society. https://www.iadisportal.org/digital-library/linking- gamification-ludology-and-pedagogy-principles-to-design-a-serious-game

Merrill’s Four-Phase Cycle of Instruction

Merrill’s Four-Phase Cycle of Instruction is best defined as the cycle of Merrill’s five instructional disciplines. It shows how the 5 principles take place in the learning process. (American College of Education, 2025). The four phases of this are activation, demonstration, application, and integration, and they cycle around the task at hand.

Merrill’s four-phase cycle of instruction in Module 2, Presentation 4

[Figure 6] Note. From American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 2 [Part 4 Presentation].

It is advised to begin this cycle with simpler tasks, especially when designing for a heterogeneous group of learners. Students must have some form of productive struggle to complete this cycle authentically (American College of Education, 2025). It is important to note that this cycle isn’t necessarily different than his five principles; this is just the framework in which they are applied.

Example

My example for this may read similarly to my example for Merrill’s five principles of design, but I will use a different context. I’m going to pull from my “almost job” experience to create this hypothetical example. Before I got my first teaching job, I was going to do recruiting. While I am a teacher now, I’ve always had an interest in LMS and ID in a non-K-12 environment.

The goal of this cycle is for new recruiters to conduct a productive interview with a possible candidate. Interviewing can be difficult, but a lot of components are pulled from experiences that many adults already have, which can make applying this design all the better for this group of learners.

Activation: Recruiters are asked about their experience with interviews. This can be as an interviewee or an interviewer. A discussion around what they feel is a productive interview will happen as well. This can put learners in the headspace of intrigue and confidence by drawing on past experiences, setting them up well for the next phase.

Demonstration: Recruiters should have productive interviews demonstrated for them, with key interview questions being identified and utilized. This demonstration should also have some backing, such as how structured questions lead “to improved interrater agreements and biases as compared to traditional interviews” (Bergelson, Tracy, & Takacs, 2022). Identifying and demonstrating the things that make the interview productive will show the recruiter what they should do and why.

Application: Recruiters will use the previously demonstrated interview techniques that resulted in a productive interview to interview other recruiters. Making them interview a candidate at this step would not be effective because recruiters need to practice the newly seen technique and see how they perform before actually integrating it into their work.

Integration: Recruiters will take this skill and use it in an interview. This interview can be with another person on the HR team, especially since they are still new to the profession. Integrating some skills in a low-stakes environment will still give the recruiter the chance to conduct a productive interview with a candidate and then apply their new knowledge in future, high-stakes interviews.

Reference(s)

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 2 [Part 3 Presentation]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

Bergelson, I., Tracy, C., & Takacs, E. (2022). Best practices for reducing bias in the interview process. Current Urology Reports, 23(11), 319–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11934-022- 01116-7

Project Management Models

Agile

Agile is a broad framework that models fall into, such as the SAM model. This approach “offers more flexibility to adapt the plan as the project unfolds and changes” (Harake as cited in American College of Education, 2025). Agile models all have iterative phases built into them, emphasizing the importance of repetitively refining tools as feedback is given. As the world changes rapidly around us, especially with technology, it is imperative that design models lend themselves to this fast-paced reality in an effective way. With agile-based models, flexibility becomes easier to attain due to their iterative nature. Implementing concepts little by little for their audience seems to be a common and productive theme, as it makes reformulating concepts a staple of agile processes and not the final step, as it is in a more linear design. Agile seems to be similar to Merrill’s 5 principles in its identification, acting as a set of concepts as opposed to a specific model like SAM or the four-phase cycle.

Example

An example of an agile approach is seen in a study done in IT sourcing. The participants used an agile approach through an IT sourcing dimensions map to make structured decisions based on their findings. This can better be described as breaking down what IT sourcing methods work best with the agile approach. The participants used the dimensions map to do so. This is where the iterative design aspect takes place. The participants don’t lay out an entire framework to figure out what sourcing method beats others at all times, but rather, which methods work the best with the agile model, and as IT evolves. They then go back to refining sourcing strategies based on the agile model. It is not a one-size-fits-all answer, but a cyclical methodology to improve their business. Amiri et al. (2021) study concluded that “organisations should recognise the effects of agile frameworks to make ITS decisions accordingly”. (Amiri et al., 2021). This makes sense as a project management model when working with multiple sourcing options and stakeholders.

Reference(s)

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 2 [Part 4 Presentation]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

Amiri, F., Overbeek, S., Wagenaar, G., et al. (2021). Reconciling agile frameworks with IT sourcing through an IT sourcing dimensions map and structured decision-making. Information Systems and e-Business Management, 19, 1113–1142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10257-021-00534-3

SAM | Successive Approximation Model

The SAM or successive approximation model is an agile approach that follows the cycle of preparation, iterative design, and iterative development. This design requires users to develop learning materials quickly and then refine them through feedback and subsequent application. This process repeats as it is based on iterative design. (American College of Education, 2025). The phases of this model are defined as follows

Preparation: This is where the designer/educator analyzes their problem and audience and questions who their audience is, what the educator needs, and what the audience needs. Allen and Sites (2012) note questions asked in this phase.

Who are the learners and what needs to change about their performance?

What can they do now?

Are we sure they can’t already do what we want?

What is unsatisfactory about current instructional programs, if any exist?

Where do learners go for help?

What forms of delivery are available to us?

How will we know whether the new program is successful?

What is the budget and schedule for project completion?

What resources are available, human and otherwise?

Who is the key decision maker and who will approve deliverables? (p. 43-44).

Iterative Design: This is where the educator or the designer makes sample materials and designs for a program. Allen and Sites (2012) encourage designers to make a new design even if it’s “frustrating”. I feel like this is an important aspect of the SAM model. It forces designers to be open and to make something. The entire process of this model cycles anyways, so you need to have something to cycle. Getting caught up in a linear approach or perfecting a design before implementation is useless in this model because it doesn’t lend itself to the rapid and repetitive process. This phase is also where old materials and designs can be used (especially if it’s something that was already designed within a previous cycle).

Iterative Development: In the development phase, “prototypes need to become more thoroughly representative of the final product” (Allen and Sites, 2012 p.45). Actual materials need to be prepared here and implemented. While there are multiple cycles of preparation, design, and development, at any iteration of SAM, design materials need to be made at this point because the next iteration needs to have material to work with.

The goal of SAM is that through every iteration of the cycle; the designer learns more about what works and what doesn’t to get to the final product. SAM has a structure with a goal; it’s just not linear.

Example

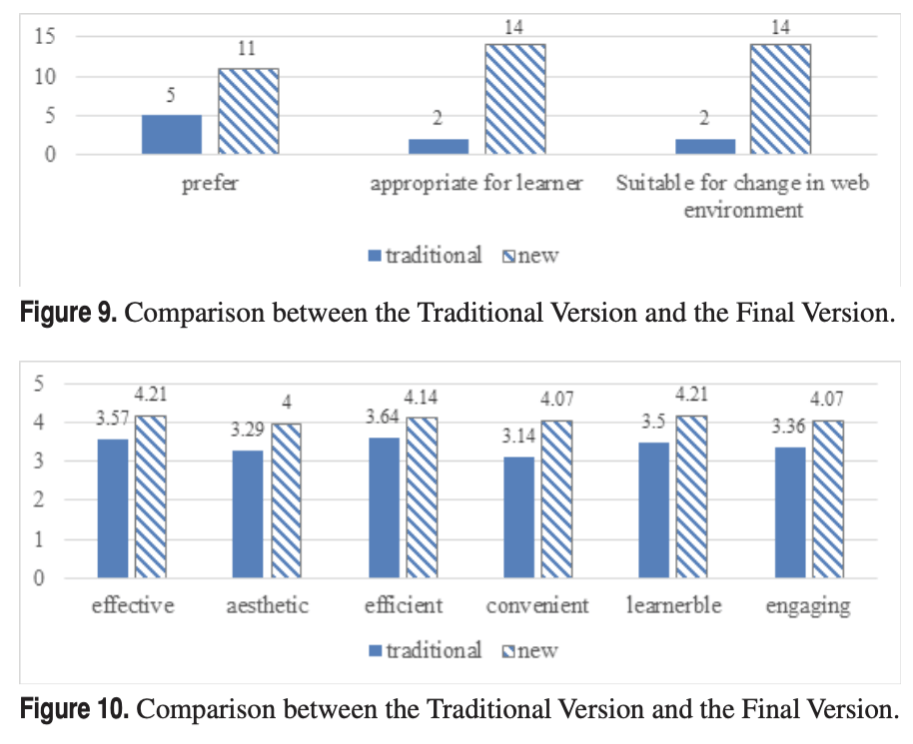

Jung, Kim, Lee, and Shin (2019), conducted a study on the impact of SAM on e-learning.

In their preparation phase, they explain that “few studies have been conducted to provide real-world examples of how SAM can be used by instructional designers to develop e-learning content” (Jung et al. 2019). This shows the importance of providing quantifiable data regarding the benefit of the successive approximation model and not just theoretical discussion. They identify the participants as subject matter experts (SME), instructional designers (ID), and prototypers. The IDs, prototypers, learners, and SME work together in the study. They were to design an e-learning experience revolving around 3D printing using the SAM. All participants brainstormed answers to questions from Allen and Sites’ book “Leaving Addie for SAM” before moving to the iterative design phase. Each person had a different role that they tackled in creating this learning platform. In summary, they stated they needed to begin lectures about 3D printing in an engaging, relevant fashion, that they needed to focus on the potential learners weaknesses, that potential learners could apply this in their own lives, and that the lectures should be 10 minutes.

In the iterative design phase, the group played off one another to complete the design process. The SMEs made the lecture and gave it to the IDs, where the ID’s then refined with the learning tools. They then created a protype of the activity that learners used and gave feedback about and the IDs further refined the prototype for the development phase.

In the iterative development phase, the group presented the “alpha” version of the e-learning tool to potential learners. After receiving feedback, the group developed their “beta” version and accommodated 2 types of learners with 2 programs (a program for learners with a basic understanding of 3D printing and a program for learners that were brand new). The lecture continually updated based on the feedback given by potential learners. The following is qualitative data garnered through the implementation of the new and refined final e-learning system.

[Figure 7] Note: Graphs from Jung et al. study detailing category changes between the traditional e-learning system and the SAM generated e-learning system

Overall, SAM was effective in the revision process, changing with learners’ needs, and grew in every potential learner’s opinion in each category.

Reference(s)

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 2 [Part 4 Presentation]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

Allen, M., & Sites, R. (2012). Leaving ADDIE for SAM: An agile model for developing the best learning experiences. American Society for Training & Development. https://www.td.org/product/book–leaving-addie-for-sam-an-agile-model-for-developing-the- best-learning-experiences/111218

Jung, H., Kim, Y., Lee, H., & Shin, Y. (2019). Advanced instructional design for successive e- learning: Based on the Successive Approximation Model (SAM). In G. Marks (Ed.), Proceedings of the International Journal on E-Learning 2019 (pp. 191–204). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/187327/

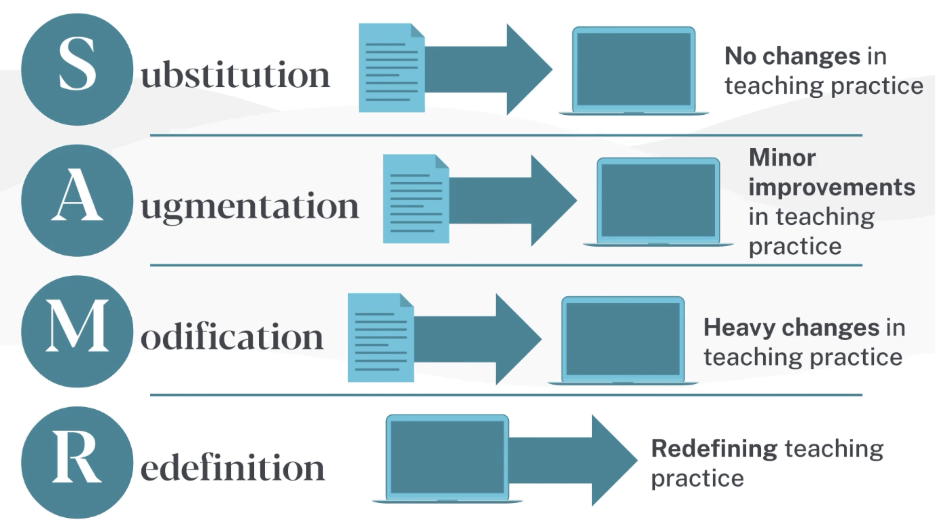

SAMR | Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, and Redefinition

SAMR is like SAM but with technology. SAMR indicates the level to which content has evolved using technology (American College of Education, 2025). The 4 parts of the SAMR model are substitution, augmentation, modification, and redefinition.

Substitution means taking content from an analog format to a digital format, with no change in the teaching practice.

Augmentation is substitution with small improvements in teaching

Modification is substitution with large improvements in teaching

Redefinition is when technology redefines the teaching practice. (American College of Education, 2025).

[Figure 8] Note. From American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 2 [Part 4 Presentation].

It’s important to note that SAMR is also a framework and not a cycle like SAM. If iterative design is used, it’s not inherent to the SAMR model but rather a combination with an agile approach. These four parts of SAMR are like a ladder and by going from the bottom (substitution) to the top (redefinition) you can get a technological product, that’s different than what you started with. You could also pick parts of SAMR to use if you don’t want to completely revamp your teaching practice and just want to enhance it with technology. Tanveer and Diwan (2021) state, “the critics of SAMR point out that it is not a ladder to be climbed and redefinition cannot be the ultimate goal of technology integration. While SAMR can be useful to encourage innovation, technology can only be as good or bad as the purpose for which it is to be used” (para. 7). Essentially, redefining your teaching practice for the sake of technology integration as opposed to the need of your clientele, isn’t the purpose of SAMR. SAMR exists to enhance learning with technology.

Example

Using the entirety of the SAMR ladder is extremely beneficial in specific contexts. For example, e-learning during the covid-19 pandemic. There was no other choice but to do learning online, so making sure that teaching practices could be done completely in an e-learning format was essential. I will use my student teaching experience during covid as an example.

The initial assignment is for students to read a chapter of a book.

Substitution: The way this would be substituted is the students read a digital copy of the book. The task stays the same, the only difference is it’s digital.

Augmentation: Students would read the book on Kami. This is an annotation site with tools to help students leave comments, highlight, and define words on the digital text. The task is almost the same but the technology provides students a chance to enhance their learning experience through digital annotation tools.

Modification: The modification for this assignment would be for students to share their document with peers and comment on their annotations to discuss each others annotations and opinions on the text. The task is fully digital and focuses more on the collaboration with peers instead of just reading.

Redefinition: In this phase, students are to work in groups to create a power point detailing how all the characters in the chapter of the book are characterized. They will use comment features on power point and Kami to identify parts of the text that relate to characterization of specific characters, and they will add those quotes into the power point under the names of the characters. This task is completely different than the initial task, and focuses solely on the ability to collaboratively identify and convey their understanding of characterization within the text through the digital tools used.

Reference(s)

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 2 [Part 4 Presentation]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

Tanveer, N., & Diwan, H. (2021). Climbing the SAMR ladder: Utilizing audio messages for teaching pathology to postgraduates. National Medical Journal of India, 34(4), 251–253. https://nmji.in/climbing-the-samr-ladder-utilizing-audio-messages-for-teaching- pathology-to-postgraduates/

Waterfall

The waterfall model is a framework that models like ADDIE fall under. The waterfall model is exactly how it sounds; designs have steps that flow into the next, like how a waterfall flows. This is a linear approach and requires steps to be completed in order before moving on to the next phase. Waterfall models are great for clarity because the team creating them knows the plan “from beginning to end” (American College of Education, 2025).

As discussed in other models, a linear process that requires sequential completion can be limiting in the design world, depending on the context and audience of the design. This is, structurally, vastly different than an agile framework, where models thrive on repetitive cycles to achieve the product. However, I’d argue that the agile and waterfall frameworks are similar in what they do. They both analyze a design problem, plan/design a solution, and create a final product, but the structure is entirely different. The Waterfall framework follows this linear order, requirements, design, implementation, verification, and maintenance.

It’s important to note that the waterfall model is an older model that has worked for decades, and it works for many reasons. The waterfall model was developed by Herbert Benington in 1956 and later coined as the waterfall model by Winston Royce in 1970 (Kalso, 2024). While this model is rivaled by the agile approach, there are real benefits to using a model like this. As stated by Kalso (2024), “the rigid, one-way structure is designed to prevent developers from continually making adjustments and additions without ever progressing toward completion” (para. 6). This model has been greatly successful when accounting for the business side of software/product development (e.g. funding for developers), something that is not always at the forefront in K-12 educational environments.

Example

An example of the waterfall model can be seen in developing a new product for a company. The goal of this model would be for engineers to develop a new vacuum.

| Step | Example |

| Requirements | The company requires that a new vacuum must have 150 air watts, be cordless, have a 4-hour battery life, and be under $250 |

| Design | The design team creates a design/layout that has the correct wattage for the size, creates the layout for the charging station, and creates the plan for where the vacuum will plug in (since it needs to be cordless). |

| Implementation | In this phase, the engineering team will make prototypes of the vacuum to make sure there are options that work with all requirements. |

| Verification | This is where the prototypes will be tested to meet the requirements. Does the battery last 4 hours? Is the wattage correct? If there are issues, it must go back to the implementation phase before moving on to the final phase, where the product is released. There shouldn’t be major issues at this point. |

| Maintenance | This is where the product is released, and the engineering team waits to see if there are any minor issues. They are corrected as needed. |

Reference(s)

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 2 [Part 4 Presentation]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

Kalso, R. (2024). Waterfall model. Salem Press Encyclopedia of Science. Retrieved from https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/computer-science/waterfall-model

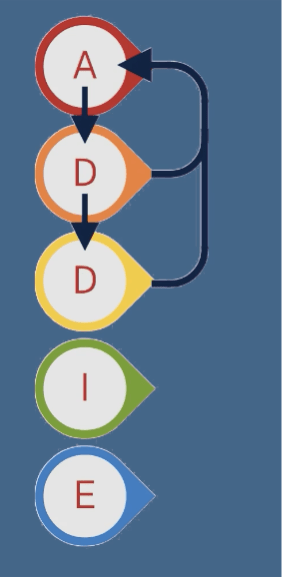

ADDIE | Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation

ADDIE is a model that falls under the waterfall framework and is used heavily in education. Drljača, Tomić, & Ris (2024) explain, “the ADDIE model is perhaps the most widely used model for developing learning materials” (para. 14). The five phases of ADDIE are essentially the same as the steps noted in the waterfall framework: analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation.

Analysis: This is where designers analyze what needs to be taught or the “goals”

Design: This is where the answer to what needs to be taught is paired with how it will be taught and assessed (the skills).

Development: This is where actual development of learning materials happens. At this step, we know what the goals and what will be assessed, but the learning materials to do those things need to be produced.

Implementation: This is where the materials created are introduced by educators to their learners.

Evaluation: Evaluation in ADDIE comes with two forms, formative and summative. Formative assessment tracks how a learner is doing, and feedback is given to the learner. Examples of formatives are checks for understanding, drafts, etc. Summative assessment is the final product that the learner creates.

As identified in the waterfall model, you can go back to the previous design to redevelop if there are issues, but you need to complete each step before going to the next (American College of Education, 2025).

[Figure 9] Note. From American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 2 [Part 5 Presentation].

Example

My example of ADDIE revolves around creating a new contemporary literature unit for an IB high school ELA sophomore class.

| Step | Example |

| Analysis | At the analysis phase, an educator would analyze what the learners struggle with and create the goal based on their findings. In this case, learners struggle with connecting IB concepts to their readings and conveying their knowledge of this. A reason why this happens is that understanding of IB concepts is best developed through student voice and discussion. Due to these findings, the goal will be for learners to engage in a Socratic seminar about how one of the 7 IB concepts is seen in the novel for the unit through a Socratic seminar |

| Design | The educator would then design how the unit will unfold and focus on the parts needed to make the unit thrive. Since the unit is centered around concepts and student voice, the framework for discussions (along with roles and weekly concept themes) needs to be created before the students begin. They are also using their findings for the Socratic seminar at the end, so there should be some form of discussion note taker and annotation tool to keep track of their own and others’ findings. |

| Development | Educators will now develop their unit using the literature circle and weekly concept focus framework. This means role descriptions, mini presentations for weekly concepts, discussion rules, and a reading/discussion calendar. If there are things that look a little off, now is the time to go back and redesign the framework for the literature circles before moving on. It is essential that the materials are completed at this step because students will be following this framework for the entirety of the unit, and it cannot be changed halfway through. |

| Implementation | This is where students are introduced to the unit and given the breakdown of how the unit will unfold. They will receive their literature circle roles and descriptions, the reading calendar, and other base materials. As each week goes on, a new concept will be introduced to them. Discussions and takeaways from the readings will occur each week, so students are to move through their reading packets progressively. |

| Evaluation | Formatives: Formative evaluations will take place through discussion preparation checks and literary circle sit-ins. Students will also be assessed formatively during a whole-class discussion on concepts at the halfway point. Summative: The summative assessment will be their Socratic seminar, focusing their discussion arguments on which concept is seen throughout the text the most. If they can engage with peers and produce a well-thought-out, evidence-backed understanding of how concepts are shown in the text, they will have met their goal. |

Reference(s)

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 2 [Part 4 Presentation]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

Drljača, D. P., Tomić, S., & Ris, K. (2024). Benchmarking instructional design models – ADDIE wins. Economy & Market Communication Review / Časopis za ekonomiju i tržišne komunikacije, 14(2), 688–698. https://doi.org/10.7251/EMC2402688D

Cognitive Load

Module 3

Cognitive Load Theory

Cognitive load theory provides a framework for understanding the mental processes involved in learning and the limitations of our working memory. Clark and Mayer (2024) define learning as a change in knowledge caused by experience. Cognitive load theory builds on this by examining how our brains process, store, and manage information during learning.

At its core, the theory recognizes that our working memory has limited capacity. When these limits are exceeded, learning becomes ineffective. The theory identifies three distinct types of cognitive load:

Intrinsic load represents the inherent complexity of the material being learned. This load varies based on the learner’s prior knowledge and the complexity of the content itself. Effective instruction carefully manages this essential processing to enhance learning (Clark & Mayer, 2024).

Extraneous load is the unnecessary mental effort caused by poor instructional design. This includes confusing layouts, irrelevant information, or unnecessarily complex explanations. As Clark and Mayer (2024) emphasize, well-designed courses minimize extraneous processing through thoughtful design strategies.

Germane load is the productive mental effort that contributes to deeper understanding. This includes activities that help learners construct schemas and apply knowledge. Courses should intentionally foster this generative processing to maximize learning and create lasting memories (Clark & Mayer, 2024).

In simple terms, cognitive load can be understood as the total mental effort required by a learner’s brain when processing new information. Instructional designers must carefully balance these three types of cognitive load—reducing extraneous load, managing intrinsic load, and optimizing germane load—to create effective learning experiences.

Example

Cognitive load theory would apply during any instructional design project. If instructors were designing online professional development for training on new gradebook software at a school, they would minimize unnecessary cognitive burdens because learners have limited working memory capacity (Sweller, 2020). The designer would manage the intrinsic load by referring to what the staff currently uses for a gradebook. The course would refer to terms and names that the staff knows and break each component into smaller bits of information. The designer would minimize extraneous load by using a variety of learning experiences. The necessary content would be concise, include well-organized images, highlight important steps, and show each step necessary. Staff could easily follow the steps needed to learn the new gradebook. The training would maximize germane load by asking staff to work in groups and practice what they are learning during the training. The professional development would include scenarios asking the staff to solve problems using the new gradebook.

Reference(s)

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2024). E-learning and the science of instruction: Proven guidelines for consumers and designers of multimedia learning. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Sweller, J. (2020). Cognitive load theory and educational technology. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(1), 116.

Managing Cognitive Load

Multimedia Principle

The multimedia principle falls under Mayer’s Principles of multimedia learning. This principle focuses on applying various forms of media to content to improve learning. The way this is done is by choosing relevant types of media that relate to the content being shown. (American College of Education, 2025). In the Nagmoti (2020) study, researchers tested the impact of the multimedia principle on traditional PowerPoints on medical students. Nagmoti (2020) discussed that “people learn better when information is presented using both pictures and words than words alone” because the brain processes information through both visual and auditory channels (p. 202). The results of his experiment reaffirmed this multimedia principle and argued that “application of multimedia principles to teach dry and complex subjects…can enhance cognitive skills” (p. 202). When looking at all the principles and models that we learn, it’s important to know the contexts where certain models make sense. The multimedia principle can be rather helpful when creating PowerPoint lessons or in lecture-based learning environments.

Example

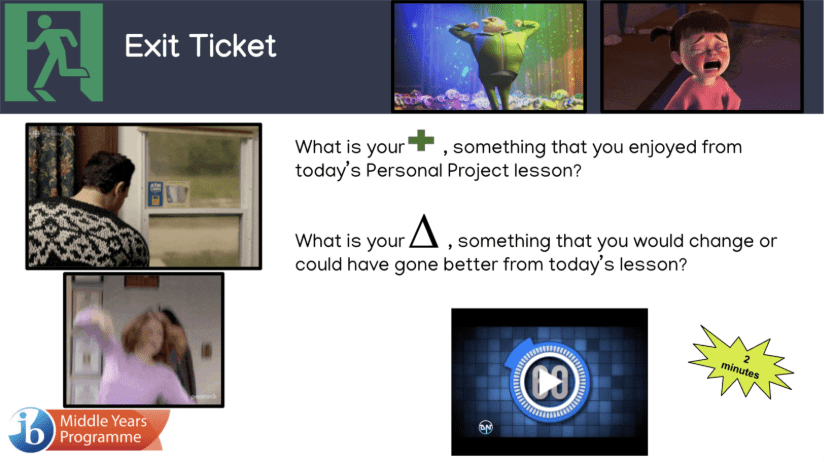

A great example of this principle in play would be during the implementation of an IB personal project through Google Slides. As a teacher at an IB school, I’m responsible for administering a Google Slide deck with information pertinent to my students about their IB personal projects. This is a project they complete on their own time, where the student’s goal is to learn a new skill based on an interest they have. It’s great in theory, but the current method of relaying this information to students is confusing, and when most of the work is done on their own, they need clear visual instructions to refer back to.

The source of a lot of issues surrounding this project is the way it is delivered. We’ve had to cut back on our IB coordinators, meaning English teachers must administer the lessons and aid students in their project creation. However, the materials are made by the coordinators, and in turn, teachers receive a Google Slide that they need to make sense of and teach. It detracts from the learning experience so much that teachers go in and remove all the various forms of media on the slides, so their students understand it better. Here is an example of a Google Slide used for an exit ticket.

[Figure 10] Example of a Google Slide not adhering to Mayer’s multimedia principle.

All the images are GIFS and are not explicitly related to the task; there are symbols in place of words that aren’t clear to the student, and the 2-minute stopwatch with the 2-minute sticker is redundant. The goal of the multimedia principle is to use visuals to improve learning, not detract from it. I have redesigned the Google Slide in accordance with the multimedia principle.

[Figure 11] Example of a Google Slide adhering to Mayer‘s multimedia principle.

I got rid of all the GIFs because they didn’t relate to the task at hand and caused more confusion. However, I still added emotion-based visuals. I made sure to use still images that are related to the question next to it, to enhance understanding of what the task is making them do.

The first task asked them about what they enjoyed, so I added a smiley face. The second task asked them to reflect (or think) about what could go better, so I added a person thinking (shown by the hand on the chin and the thought bubble with the idea lightbulb). I also changed the color of the symbols and made them flatter, so they would associate the green visual with positive and the yellow visual with a yellow light (changing).

I kept the reminder that this is a two-minute task, but it’s placed right below the now middle-aligned “Exit Ticket” header. I added bullet points to visually separate the two tasks and brought the IB logo down in size and aligned it in the right-hand corner, so it’s the last thing the eye sees. The student still has different types of media (images, symbols, bullets, text boxes), but it’s done in a way that enhances their learning experience.

Reference(s)

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 3 [Part 2 Presentation]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

Nagmoti, J. M. (2017). Departing from PowerPoint Default Mode: Applying Mayer’s Multimedia Principles for Enhanced Learning of Parasitology. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology, 35(2), 199–203. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmm.IJMM_16_251

Signaling

Signaling is also one of Mayer’s principles of multimedia learning. Signaling is using written or verbal cues to highlight information (American College of Education, 2025). Examples of these cues are stressing words in a sentence verbally or even in writing (like this), underlining sentences or phrases, using arrows in visuals, symbols, and more. (Wouters, Paas, & van Merriënboer, 2008). It’s important to note that when reducing cognitive load through Mayer’s principles, the learner needs to be able to connect the verbal information to visual information. This connection happens through signaling and understanding high and low visual search. High visual search happens when a learner is searching for what visual information connects to the written/verbal information. Low visual search is when the learner can immediately identify what visual information connects to the written information. An easy example of this is a bullet point. Cognitive load is reduced when the learner can easily identify how the visuals apply to the written content. (Wouters et al, 2008). Think about the different types of cognitive loads, intrinsic, extraneous, and germane. If a reader is not signaled correctly, the extraneous load is too much, and the learner will not be able to retain the needed information given.

Example

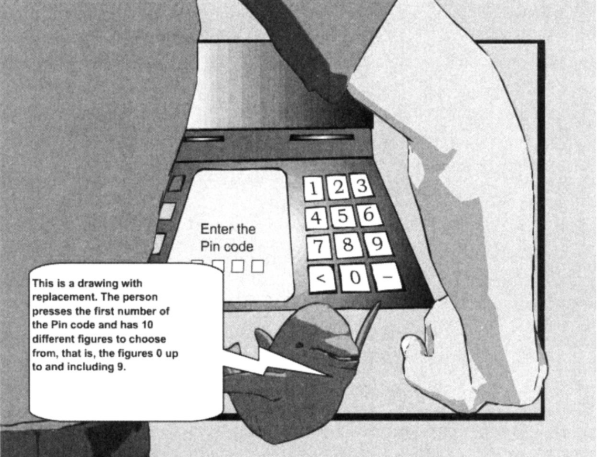

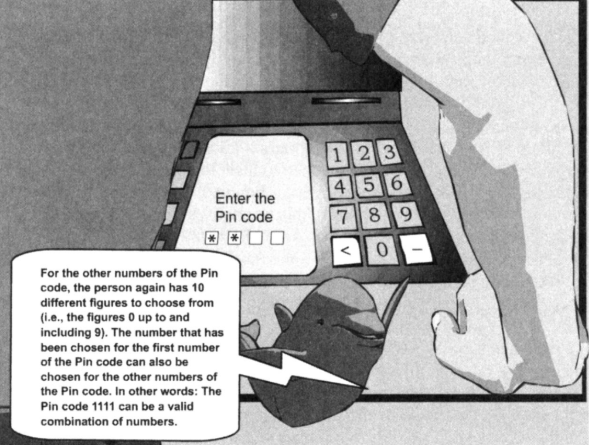

An example of signaling being seen is in a visual from the Wouters et al (2008) review on optimizing learning. In the article, the researchers are discussing replacement theory using a visual of someone at an ATM putting in a PIN number. Researchers detail the importance of strategies like signaling to optimize the understanding of complex concepts. Replacement is a part of understanding probability. This would most likely be discussed in a course or workplace that focuses on probability. Probability and actuarial sciences are complex topics, so maximizing understanding using multimedia principles is a great choice. The model below applies signaling to aid in the learner’s comprehension of replacement.

[Figure 12] Example from Wouter et al.’s (2008) study where cognitive load management strategies are applied.

In this figure, the animation has a large comment box attached that shows where a PIN code is entered. The first model is drawn from the perspective of the learner, relieving extraneous load of searching for where to look. In the second model, the numbers that the learner can use for the ATM are highlighted, signaling the learner to look towards the PIN box. There are also PIN numbers that are already punched in (signaled by the asterisks on the screen). Since all the numbers are highlighted and there are already numbers punched in, it visually shows the learner that any of the PIN numbers can be pressed for the code, regardless of whether a certain number has been pressed before (aka replacement). This model explicitly relates to the explanation given by the animation. The verbal and visuals match with low visual search, reducing cognitive load through signaling.

Reference(s)

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 3 [Part 2 Presentation]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

Wouters, P., Paas, F., & van Merriënboer, J. J. G. (2008). How to Optimize Learning from Animated Models: A Review of Guidelines Based on Cognitive Load. Review of Educational Research, 78(3), 645–675. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40071140

Chunking

Chunking, also known as segmenting, is the process of breaking large amounts of content into smaller, more manageable pieces of information. Chunking is also a part of Mayer’s principles of multimedia learning. People’s working memory has a limited capacity, so instructors cannot give a large load of information to their learners and expect them to retain all of it. (American College of Education, 2025). Through chunking, instructors can organize a large amount of information into small “chunks” or segments, so it is easier for the learner to retain all the information needed. This doesn’t mean the learner is given less information; they’re just given the information in a more concise and paced fashion. Chunking or segmenting can be done by both the learner and instructor but typically occurs with the instructor. For example, if a learner is taking notes on a presentation, instead of writing whole paragraphs, they’ll identify the main points (Castro-Alonso, de Koning, Fiorella, and Paas, 2021).

[Figure 13] Diagram explaining chunking from the American College of Education module 3 presentation.

The circle or sum of information is the same, but it’s organized into segments so learners can retain part of the content before moving on to the next segment. Chunking helps manage intrinsic, extraneous and germane loads. Learners’ intrinsic load is relieved by not having complex information flooding their learning. Extraneous load is also relieved by focusing learners on what they need to know through small segments. The germane load is relieved by the actual process of learning becoming simpler in terms of mental expenditure.

Example

Chunking is something that can be done by both learners and instructors alike. There are two examples of this seen in Castro-Alonso et al. (2021) article. There are learner managed ways of chunking and instructor managed ways of chunking. An example of learner managed chunking is seen with learners moving chunked text to corresponding visuals. The article discussed how learners could move paper cut-outs of chunked texts to a visual example or (if done digitally), by moving digital chunked texts with a touchscreen or cursor. (Castro-Alonso et al., 2021). This example pairs multimedia with chunking principles to optimize learning. Learners view complex information in small amounts (chunks) and connect said chunks to visual representations. In the instructor-based chunking example, instructors break down visual learning by pacing videos presentations. Chunking is not only bulleted versions of the written word, but also the pace at which a student learns information. The instructor provided “segmented animations with necessary interspaced lapses of time…to allow working memory to replenish before additional information is shown” (para. 46). A large or complex presentation was broken down into different animations and intentionally provided space between the next piece of information. The use of chunking through spacing or timing serves to help the learners mental load “replenish”. The study was able to conclude that students that were shown the chunked or segmented version of videos actually outperformed the students shown unsegmented videos, further enforcing the importance of chunking to ease cognitive load. (Castro-Alonso, 2021).

Reference(s)

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 3 [Part 2 Presentation]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

Castro-Alonso, J. C., de Koning, B. B., Fiorella, L., & Paas, F. (2021). Five Strategies for Optimizing Instructional Materials: Instructor- and Learner-Managed Cognitive Load. Educational Psychology Review, 33(4), 1379–1407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09606-9

Visual Cognitive Load/C-R-A-P

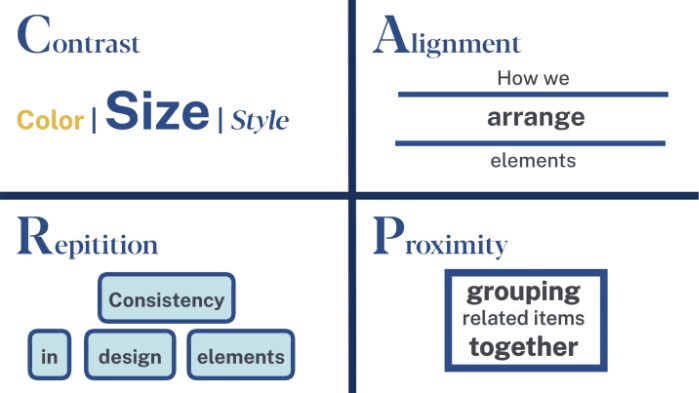

Visual cognitive load refers to the “mental effort required to process visual information” (American College of Education, 2025). By understanding this, instructional designers can maximize the impact of visuals on learners. C-R-A-P; contrast, repetition, alignment, and proximity, is the acronym used when making visual materials. This management of visual load is used to prevent the learner from becoming overwhelmed and to appeal to the learner. Mayer’s multimedia principles are very similar to C-R-A-P, but their purposes are slightly different. C-R-A-P is the overarching framework for how to make visuals appeal to a learner. Mayer’s principles focus on optimizing learning and how learner benefit (performance and understanding wise) through the use of multimedia. C-R-A-P is for effective appeal, and Mayer’s is for cognitive performance. Many times, these two principles work together to create learning materials, but they do tackle different things. For example, well-designed visuals contribute to learning effectiveness, but the material being learned in the multimodal format can be made with Mayer’s design principles.

C-R-A-P is broken down as follows:

[Figure 14] Diagram illustrating C-R-A-P from the American College of Education module 3 presentation.

As stated earlier, these design principles are not stand alone and are intended to work with other design principles. An article from Chen and Mokmin (2024) analyzed the use of digital visual materials in Chinese primary school environments to improve cognitive load. They discuss how the creation of the materials must be thematically relevant to the content discussed, focusing on C-R-A-P principles like color and repetition to create their design. This doesn’t directly discuss Mayer’s principles of multimedia design, but more so focuses on how aesthetically effective visuals go hand in hand with optimizing student learning (Chen and Mokmin, 2024).

Example

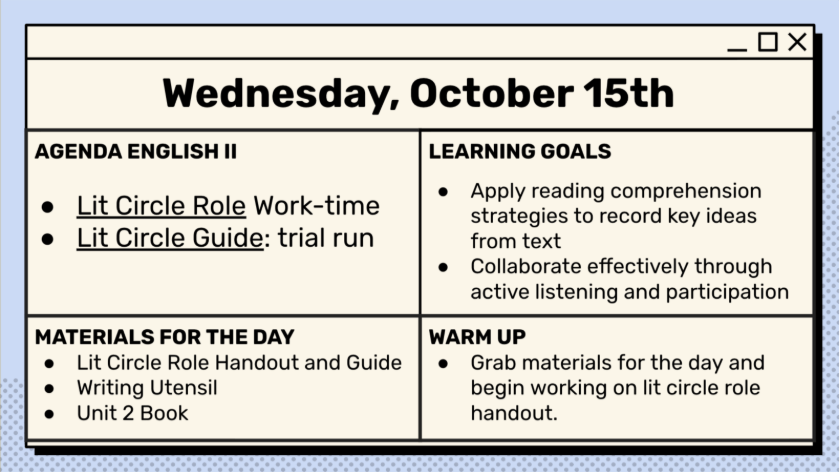

An example of C-R-A-P seen for visual cognitive load management can be seen in daily PowerPoints/Google Slides used by teachers. Many educators use Google Slides that they think are visually appealing, but they may not be effective for learning. It’s important to pair these two ideas together when understanding visual cognitive load and principles of C-R-A-P. While C-R-A-P does focus on aesthetics of visual learning materials, there is purpose behind considering those aesthetics; a student’s ability to have content effectively communicated to them. Below is an example of my daily slides for students in an English Language Arts course.

[Figure 15] Example of C-R-A-P principle applied Google Slide to manage visual cognitive load.

There is typically an overload of information given at the beginning of a class. Students need to know what they’re doing for the day, the goal of that learning, what materials they need, and time to settle. Because of this, I section my daily slides like above. Students come in at different times, so a verbal explanation will not suffice when introducing daily activities, goals etc. Here is how C-R-A-P is seen on the slide.

Contrast: The background color of the slide is a light cream color with black lettering, providing visual contrast for the student. There is also a contrast between the size of the text, with the labels in all caps, and the agenda items in a larger text. This contrast guides students to what will be expected of them, and the content is legible. The data is the largest, anchoring the materials to that specific date. The style of the font didact gothic, which is personable, inviting, and legible.

Repetition: The boxes repeat and so do the tasks for each box. There are bullet points between each expectation, guiding the reader through each box. The slides for everyday use this same format, making the formatting consistent for the student by day as well. Along with this, the tasks all relate to one another. It shows what, why, and how the students will be doing the task assigned, repeating the purpose of the day.

Alignment: The text is aligned to the left in each box, guiding learners to read from left to right for both the box and the slides as a whole. The header is centered, acting as the anchor point, with the tasks aligned in boxes evenly below.

Proximity: The text written is related to the task listed in each box. Students do not have high visual search, and the explanation for each header is directly below the header itself in the same box. All the materials and goals for the day are listed on the same slide, that way students can find everything needed for class that day, in one place.

Reference(s)

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 3 [Part 2 Presentation]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

Chen, J., & Mokmin, N. A. M. (2024). Enhancing primary school students’ performance, flow state, and cognitive load in visual arts education through the integration of augmented reality technology in a card game. Education and Information Technologies, 29(12), 15441-15461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12456-x

Strategies for Student Learning

Scaffolding

Scaffolding is a teaching strategy that uses student supports based on their understanding. Typically, units are scaffolded with multiple student supports at the beginning and then less supports as the students gain confidence in the material. The presentation described scaffolding like “training wheels” (American College of Education, 2025). When looking at how scaffolding can be done, we can look at cognitive learning principles and strategies. For example, chunking is one of Mayer’s multimedia design principles, but it can be used to help scaffold content for learners. Chunking is the tool, but scaffolding is the overarching strategy being used.

Scaffolding is beneficial to all learners, but especially learners of varying understanding. Hendrayana and Mutaqin (2025) identify that “recent studies confirm that scaffolding is particularly beneficial for learners with low or intermediate prior knowledge, enhancing their ability to regulate their thinking and sustain attention engagement” (para. 10). Using scaffolding as a framework and applying varied supports to students of varying skill levels is a key use of this teaching strategy.

Example

Scaffolding seems to be effective in a K-12 environment, with all subjects being able to apply it across a diverse body of learners. My example of scaffolding revolves around my Journalism-Yearbook course. There are so many skills that a student new to Journalism-Yearbook needs to learn, but familiarity with each of the skills is dependent on each student’s prior knowledge and skill levels. With such a large skill requirement and differing levels of understanding amongst students for different skills, scaffolding is a must when creating an introductory unit.

In an introductory unit for Journalism-Yearbook, there must be a scaffold for each new skill. I’d use chunking to section the skills into new weeks. Let’s focus on the reporting aspect of the unit. I would introduce the class to what reporting is in relation to yearbook on the first day. I will provide the basics such as what a reporter does and show an example interview. I’d do a quick assessment as well to see where students lie skill-wise to provide better support throughout the week. The next day I would have students create questions to interview one another. Students that are at the lowest level will have prompts given to them; students at higher levels would create their own questions for interviews. On the third day I would have students do peer interviews with someone on the same level to practice their questioning and discussion abilities. On the fourth day, students would draft a mini story about the interview they engaged in the day before. All students will receive the option to use a story template, and there will be an option for learners who want to write a longer story to interview more peers who would like to add to their stories as well. This gives much needed support to both groups. At each level, I would provide feedback as I sit in on different learner’s interviews and writing time. On the final day, students would assess their own stories using a rubric and make changes if need be. Students who need more support can review peers as well.

In this scaffolded week, each skill level is provided an outlet to exercise their learning differences and the steps of reporting and writing a story are broken down into day periods, with the end goal being understanding how reporting works.

Reference(s)

American College of Education. (2025). TECH5203 Fundamentals of learning design and technology: Module 3 [Part 3 Presentation]. Canvas. Retrieved from https://ace.instructure.com/courses/2120149/modules/items/44638812

Hendrayana, A., & Mutaqin, A. (2025). The Effectiveness of Problem-Based Learning through Scaffolding in Enhancing Problem-Solving Skills of Students from Diverse Prior Knowledge Levels. Educational Process: International Journal, 16, e2025275.

https://edupij.com/index/arsiv/77/646/the-effectiveness-of-problem-based-learning-through-scaffolding-in-enhancing-problem-solving-skills-of-students-from-diverse-prior-knowledge-levels

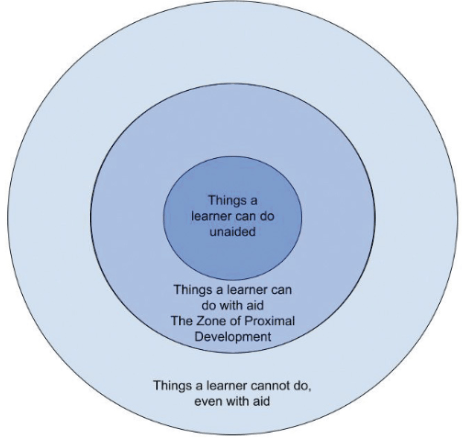

Levels of Challenge

Levels of challenge is a teaching strategy that uses Vygotsky’s ZPD (zone of proximal development). The zone of proximal development aids in the process of introducing tasks to learners without overwhelming them. A designer must know the ZPD of a student before giving them a challenge appropriate task. If you don’t know where a student lies, there’s no way of knowing if the task is appropriate or not. Like scaffolding, ZPD is especially helpful when dealing with a diverse body of learners. Both strategies focus on providing supports for students, but levels of challenge can work alongside scaffolding when deciding what materials are needed for students. Coles (2025) article explains how ZPD actually “highlights the importance of scaffolding” (para. 6).

Levels of challenge is imperative to learner success. Understanding ZPD is essential to providing levels of challenge to all skill levels.

[Figure 16] Figure of ZPD from Coles (2025) article

As seen in the example, the zone of proximal development is sandwiched between what the learner can and cannot do. If they can do the task without an aid, it is outside of their ZPD. If a learner cannot do a task, even with an aid, that task lies outside of their ZPD. Like goldilocks and the three bears, the task needs to be just right. If they keep doing tasks that they can already do, they won’t grow; if they do tasks that they can’t do, they won’t have the necessary prior knowledge to even attempt growth. For example, a student’s math knowledge compounds the more they learn new skills. If a student cannot do algebraic equations (simplify expressions / understand functions), they won’t be able to comprehend calculus because calculus is based on functions and simplifications.

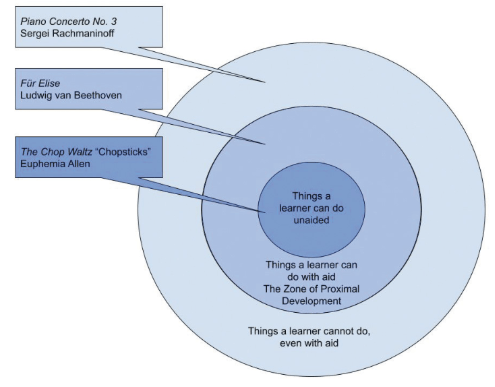

Example

An example of levels of challenge can be seen in Cole’s (2025) study of avocational pianists learning piano using the zone of proximal development. Anyone that is considered a beginner avocational piano player has their ZPD broken down like figure 17.

[Figure 17] Example beginner avocational piano player ZPD from Coles (2025) article